An attempt to think through the connections between state debt, social reproduction and class struggle in Australia

In part two of Australia You’re Standing In It I’m going to attempt analyse the relationships between state debt and social reproduction. In particular I want to argue that rising debts and continuing deficits provide a challenge to how social reproduction is carried out by the state. This directly flows on from the previous chapter as the core of my argument is that the rising debt and deficit of the Australian state are at least in part a product of the global stagnation of capital accumulation. This manifests in the drop in revenue caused by the winding down of the mining boom.

I want to emphasise the stakes of my argument. In mainstream debates in Australia debt is most often framed in one of the following two ways. For the Right debt is a cause, if not the cause, of economic stagnation and crisis. For the Left Australia’s debt levels are unproblematic and the panic over debt is a production of the fetid imagination of the neoliberals and/or a cynical manoeuvre to justify the sort of policies the Right always carry in their back pockets. Here I wish to reject both these arguments. Debt is not the cause of crisis but a particular manifestation or expression of it; but it is a manifestation that has its own contradictions. And debt levels whilst overblown by the Right do present a serious challenge to the state’s abilities to finance and carry out social reproduction. Also a new revelation for me, one often ignored in the debates about debt, but one that is obvious when you think about it, is the role that sovereign debt in the form of state bonds plays in the financial markets. The debate over state debt is also always a debate about securing the value and the profits generated by financial assets.

A limitation of my investigation so far is that since my methodology looks at the movements of capital from ‘above’ there is the risk that I can slip into a form of presentation that ignores the class struggle that goes on ‘below’ and throughout capitalism. There is a danger, from Marx on, that our analysis can be too ‘objective’ and not grasp the subjective role struggle plays in the corresponding unfolding of the dynamics of capitalism(Shortall 1994). (Perhaps it is possible to see class struggle as the struggle of humanity against its entrapment in the objective categories of capitalism). My challenge is to express how the ways the state funds social reproduction and the shapes social reproduction take are products and sites of class struggle. Spiralling state debt is an expression of our power – even if it is latent. We need to enlarge our understanding of class struggle beyond a model that sees it primarily happening within the confrontation between labour and capital in the work-place proper, that is move beyond a ‘factory-office-farm’ model (Caffentzis 2013, 242). We need to understand the complex and multifaceted struggles that happen across all of society.

Debts and Deficits

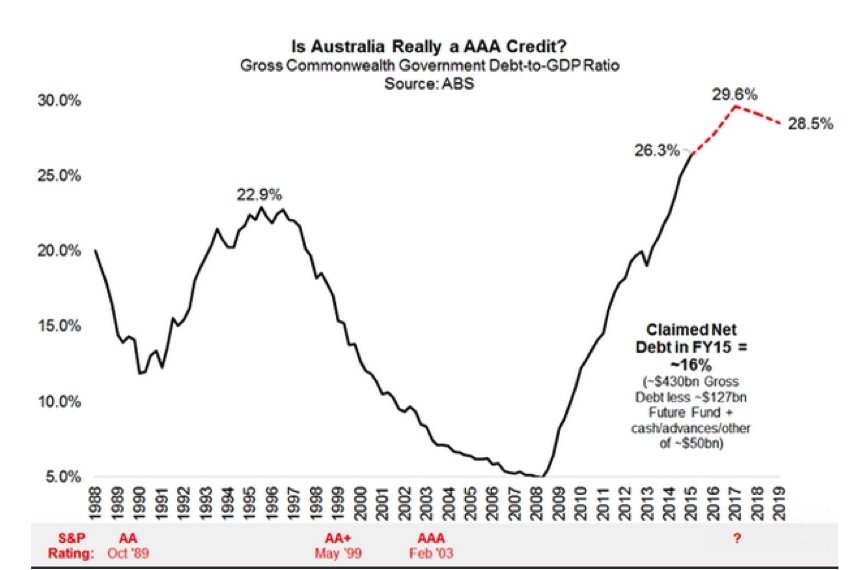

Both the debts and the deficits of the Australian Federal and State governments (on a whole) continue to grow. The Federal budget will be in deficit till at least 2019 (based on current predictions). However these projections are premised on predicted volumes of LNG gas sales that are perhaps too optimistic, they assume that no tax cuts will come through in the future and that slated budget cuts are implemented (Business Council of Australia 2015, 4, Daley and Wood 2015 , Parliamentary Budget Office 2015). ‘Net debt is projected to increase from $250.2 billion in 2014–15 (15.6 per cent of GDP), to peak as a proportion of GDP at $313.4 billion (18.0 per cent of GDP) in 2016–17, before declining to $201.0 billion in 2025–26 (7.1 per cent of GDP)’ (Parliamentary Budget Office 2015, 2). Gross debt is projected to increase from ‘59 billion in June 2008 (or 5 per cent of GDP) to about $430 billion by June 2015 (26.3 per cent of GDP). This excludes another $275 billion of government debt owed by the states, local authorities and public companies’(Joye 2015).

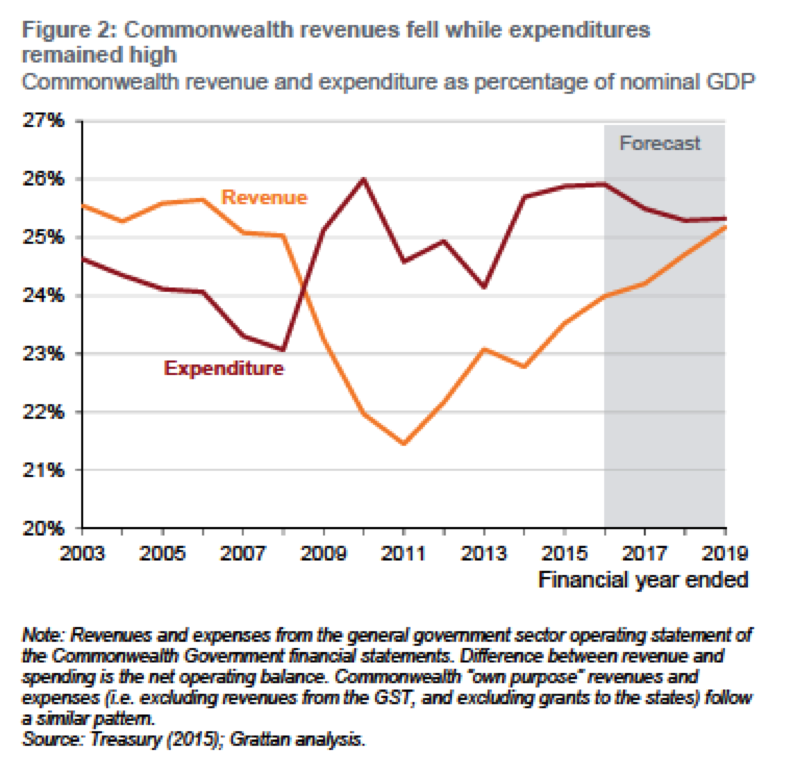

The cause of this debt is structural: declining growth of revenue in comparison to growth of expenditure. The global crises hit incomes and thus revenue, so too the end of the mining boom, a condition of the global crisis, has also undermined incomes and thus revenue whilst an aging population and marginal increases in unemployment means an increasing expenditure on social welfare.

At the onset of the crisis revenue dropped whilst spending increased and since then both have only moved slowly towards alignment. ‘Spending has grown by around 3.6 per cent per year in real terms over the past decade, much higher than average revenue and economic growth’ (Business Council of Australia 2015, 3). Social security and welfare spending contributed about a third of the growth in spending over the decade. ‘Growing Age Pension payments are the biggest contributor, but health, education and general public services, all of which grew faster than GDP, also increased significantly’ (Daley and Wood 2015 6).

The general mainstream consensus is that the end of the mining boom will mean a decrease in revenue; as will an aging population as a larger proportion of the population will leave the workforce (and thus income taxes will drop). The end of the mining boom has already seen a step down in revenues ‘Over the 2000s, record terms of trade fed bonanza revenues of more than 25 per cent of GDP. They should never have been expected to persist. Revenues are ‘normalising’ to a post-terms-of-trade-boom economy, at around 24 per cent of GDP’ (Business Council of Australia 2015, 4). An aging population will also increase social welfare; so too the ‘National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), the Families Package, and the Direct Action policy to address climate change, and commitments to increase defence spending. Together these signature polices are likely to add more than 1 per cent of GDP to spending over the decade’ (Daley and Wood 2015 8). The spending costs of aged care will probably grow even more in the period that is just beyond current budget forecasts (Business Council of Australia 2015, 20) Thus it seems probably likely that debts and deficits will continue to grow – and that is before we factor in the possibility of another global shock.

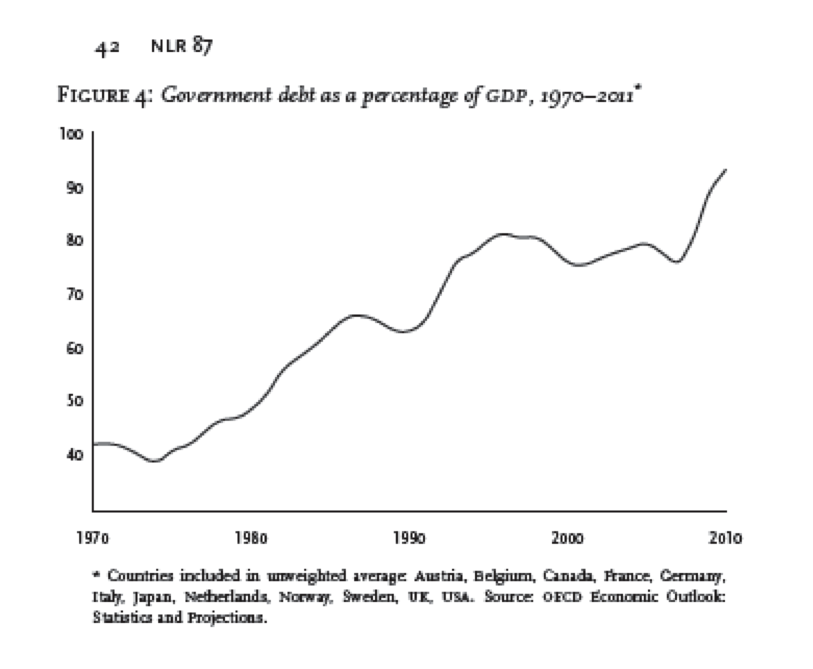

That said the level of Australia’s debt is comparatively low; with ‘net debt only 15 percent of GDP compared to 79 percent on average for G20 advanced economies’(International Monetary Fund 2015, 4) . Also the Australian experience differs remarkably from the rest of the Global North. Painting with a broad brush we can say the state debt of many states in the North have been growing since the early 1980s at least.

Whilst in Australia the revenue from the mining boom meant debt declined before recently rocketing back up.

Is debt then a problem? The debates over the level of government debt and deficit normally take the following form: those on the Right argue that debts need to be reduced and those on the Left who argue that debts aren’t as important as productive investment. Without a doubt the rhetoric of the Right on debt has been overblown; but we still need to understand that rising debts and deficits present a challenge, a series of conflicting priorities for the state and the way it tries to ensure the reproduction of capitalism in Australia. Debt currently impacts on the state’s ability to reproduce capitalism in Australia. It does so because the Australian state needs to do multiple contradictory things. It is driven to ensure the viability of meeting its debt obligations and the viability of debt as an asset, ensure the provision of social reproduction at a level that allows the smooth accumulation of capital and to also carry out stimulative activity. In the context of the contemporaneous drop in capital accumulation and the rise in debt the state needs to spend more and spend less simultaneously.

What seems to be a technical question is in fact the appearance of antagonistic social relationships. This is one of the realities of capitalism: human dynamics, social relationships, become embodied and objectified in things. The basic unit of the capitalist mode of production is the commodity-form in which social relations take ‘the fantastic form of a relation between things’(Marx 1990, 165). Capital itself is a ‘definite social relation of production pertaining to a particular historical social formation, which simply takes the form of a thing and gives this thing a specific social character’ (Marx 1991, 953). Debt is a form of ‘interest bearing capital’: that is the lending of money as a path of accumulating capital. Here ‘the capital relation reaches its most superficial and fetishized form’ (Marx 1991, 515). We must also remember that these social relations are exploitative and antagonistic. The debate then about sovereign debt between the Right and the Left then misses the point. Debt isn’t simply a question of finding the right volume or level as if one was pouring a glass of water. Its technical and cold character is the form that a conflict between people takes. Debt is a question of class struggle. But to grasp this we must go beyond the standard inherited image of what class struggle is.

The State & Social Reproduction

We need to understand what the capitalist state does to reproduce Australian society as a capitalist society, what the relationship is between state debt that takes the form of bonds and the broader financial markets or credit system and the role this plays in ensuring accumulation on a whole.

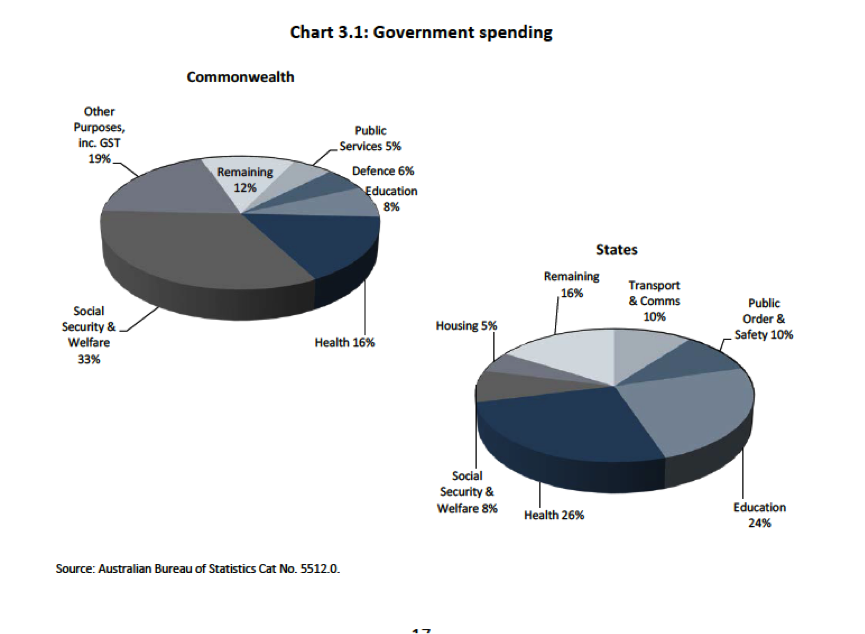

What is it that the state does? It works to ensure the reproduction of society[i]. This implicitly means the reproduction of society as a capitalist society: a society organized around the accumulation of capital and in which the accumulation of capital is possible. This involves a vast variety of different tasks that encompasses the broad work of keeping the society functioning in an ordered way as well as activities aimed at directly stimulating and encouraging capital accumulation. The manifold ways that we are policed, managed and organized by the state is key to this. The 2014 National Commission of Audit details the relative shares of government spending as follows:

(2014, 17)

(2014, 17)

Obvious examples of social reproduction that the state performs are the work the public service does from producing accurate statistics, building (or not as the case maybe) a broadband network to funding psychological counseling and everything in between. This of course costs: and thus the state raises taxes, owns income generating assets and makes investments as well as borrowing money. The precise share and forms of revenue raising, stimulation and reproduction makes up a great deal of what passes for politics in capitalist society as different ideologues, parties, interests and industries make competing claims and sketch various visions of what a desirable form of capitalist society looks like.

The activities that the state carries out make up only part of the work of social reproduction. A great deal of the work of reproducing human beings as workers and citizens, as repositories of labour power, is still performed largely by women, unwaged and in the home. Indeed the very concept of social reproduction as a critical tool for understanding society arises out of the insights of feminism about the crucial importance of unwaged work of women (Dalla Costa and James 1975, Federici 2012, Fortunati 1995). When we say social reproduction we generally mean all the forms of human activity that are necessary to keeping capitalist society going but are parallel to direct activities of capital accumulation which in and of themselves also contribute to the reproducing a capitalist society as a capitalist society. However the borders between the activities of capital accumulation proper and that of social reproduction are often so porous as to be indistinct, as are those between different forms of reproductive labour. Walk into any public service office and you will find multiple points of private capital accumulation: contracted cleaners, photocopy services, the Coke machine…

The current provision of welfare services often involves funding by the state to non-profit NGOs who compete in strange forms of ersatz markets often promoting their ability to use unpaid volunteers as a way of providing services.[ii] With the rise of social impact bonds many of these activities will be come points of financial speculation and profit. So too the increased entry of private health companies into the provision of the back of house for Medicare or their future plans to be involved in the organization of the NDIS transforms these functions into direct sites of accumulation. Thus social reproduction takes the form of a complex web made up of the state, NGOs, private companies and unpaid labour of carers and volunteers (most often women). The recent Harper Competition Policy Review wants to further extend this tendency. The state, it argues, should maintain only a ‘stewardship function’ whilst ‘A diversity of providers should be encouraged, while taking care not to crowd out community and volunteer services’(Harper et al. 2015, 262) .

It is then an error to understand the shift from (what is problematically called) social democracy to (what is problematically called) neoliberalism as the retreat of the state.

'The ‘retreat of the state’ was popularised by neoliberal ideologues in response to the failure of big-spending Keynesian policies to resolve the stagflationary crisis that ended the long post-war boom in the 1970s. Markets, private enterprise and reduction of government intervention in the economy were supposed to replace ‘bloated’ welfare states. Yet OECD data shows that tax revenue as a proportion of GDP actually rose in member states over the period 1985 to 2007, from 32.4 to 35.0 percent. This trend also holds across the four Anglophone countries that supposedly went furthest and earliest down the neoliberal road — the US, UK, Australia and New Zealand. Some of this revenue went to direct corporate welfare, but in most countries there were also rises in social spending, even if in some cases service delivery was increasingly placed in private hands or under ‘efficient’ market principles. Overall, OECD governments increased social expenditure from 17.2 to 19.7 percent of GDP between 1985 and 2005.' (Tietze and Humphrys 2015)

What has changed is the way the state operates in the complex networks of providers of social services and the subjective and ideological experience of being in these services. Lorey (2015) argues that there has been a shift from social spending operating as a blanket form of security to all citizens ( and thus policed and separate from non-citizens) to a contingent set of minimums organized in a hierarchy; a precarization as a way of governing the population. There are complex sets of services and payments one can access based on a complex set of criteria and measurement’s of one’s behavior.

A key understanding, drawing on the feminist insights of wages for housework, is that all these forms of labour are both crucial to the continuation of capitalism generally and the accumulation of capital specifically and are also the terrain of conflict, struggle and potentially emancipation (Federici 2012). The history of the transformation of how social reproduction is carried out throughout society generally and the size of the state’s share of this labour and its specific forms are thus questions of struggle. Broadly speaking we can understand the shape social reproduction takes as the product of long waves of struggle. In the 20th century there was the original Keynesian intervention to provide the social wage as attempt to contain proletarian struggles within capitalism(Hardt and Negri 2003). The rebellion of the 60s and 70s, specifically that of women, refused the imposition of unpaid reproductive labour in the home, invented new feminist organizations of care provision and placed increased demands on the state (Federici 2006, 2012). And then the counter-revolution of neoliberalism which saw in no small part the transformation of some aspects of social reproduction into profit-making industries, the afore mention transformations in provision, the proliferation of user-pays/ debt for health and education and what not. At the same time recipients of welfare services such as for those with disabilities and their supporters, carers and loved ones have also been able to reshape the provision of services in ways that increase their quality of life and autonomy. (The critiques of neoliberalism nor nostalgia for social democracy shouldn’t blind us for example that the kind of life a young person with Down Syndrome can have in Queensland today is, in many ways, remarkably freer than it was in the 1960s).

Today the state’s difficulties in financing social reproduction are an expression of its inability to sufficiently lower our expectations for life – to effectively wield repressive power. The challenge for the state is to try to carry out social reproduction that will hold Australian society together in a way that allows capital accumulation to continue and that can be paid for in a way that doesn’t impact on capital accumulation on a whole. Whilst for us the challenge is to assert our needs for dignity and justice despite and against what capital on a whole and the state specifically can pay for – as part of our struggle inside-against-and-beyond capitalism.

Taxation

Faced with growing expenditure and declining revenues it seems obvious that one of the solutions is to increase revenue: to increase taxation. It is no surprise that the Left, who often view taxation as a form of progressive wealth redistribution, have been making this case. John Passant a prominent socialist blogger and former Assistant Tax Commissioner has being making the point that it would be easy to raise funds equal to or greater than the deficit by increasing taxation on the wealthy.

'A government with guts could reverse that. It could champion taxing the rich till their pips squeak. If nothing is truly off the table, then a net wealth tax of 2% on the top ten per cent of wealth holders in Australia could raise up to if not more than $30 billion a year. Is a net wealth tax on the table Mr Turnbull?

What about estate and death duties, Mr Turnbull? Are they on the table? Gina Rinehart, James Packer and even Rupert Murdoch didn’t get rich through hard work. They inherited their initial wealth.

The current superannuation tax concessions forgo almost $40 billion a year, and 57% of that revenue forgone goes to the top 20% of income earners. Scraping the concessions for them has the potential to raise about $20 billion alone.

Of course, these rich tax leaners would look for other lurks to reduce their tax. Investing in negatively geared properties, shares and so on would be one option. So, a government with guts would get rid of that too. This has the potential to raise around $5 billion a year.

Another option for the tax leaners if these avenues were closed off would be to invest even more in the family home. A government with guts would include family homes sold for more than, say, $2.5 million in the capital gains tax.

If a person holds an asset for more than 12 months and then sells it, only half the net gain is taxed under our capital gains tax. The top 20% of income earners make 80% of capital gains, so abolishing that concession would be both just and equitable and raise billions.'(2015)

Leaving aside what role a ‘government with guts’ has in our self-emancipation the argument that is would possible and produce a more equitable outcome seems correct. The problem however is that capitalist societies are societies build around the accumulation of capital not just unequal piles of wealth; even if the latter is a product and a precondition of the former. For the state the question is always how to fund social reproduction in a way that minimises the impact on capital accumulation. The state itself is dependent for its functioning on capital accumulation. This is not simply the outcome of a neoliberal ideology but is a material reality.

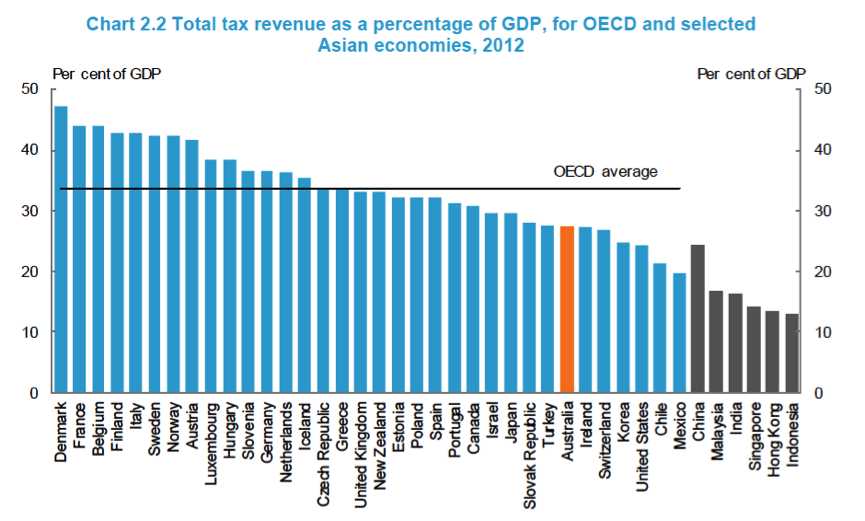

As such the concern of the state is to shape policy in a way that stimulates capital accumulation. And if capital accumulation is driven by the investment of firms seeking to make a profit tax policy needs to be shaped in a way that ensures or increases profitability. The main thrust of current tax reform discussion is about shifting more of the burden of tax from capital to labour in particularly through increasing consumption tax in the form of the GST whilst cutting corporate taxes. This is the case is being made by various factions for capital. The government admits that compared to other similar countries the tax burden in Australia is light.

(The Australian Government the Treasury, 17)

(The Australian Government the Treasury, 17)

However they argue that the level of corporate tax deters investment. ‘As the mobility of capital increases, Australia’s high corporate tax rate can deter investment, ultimately leading to lower wages and prosperity’(7). PwC (2015)channeling the Laffer Curve argue that a cut to corporate tax, because it would spur investment would lead to an overall increase the in the amount of money raised. Lower taxes = more investment = more state revenue the argument goes.

Who knows? Opponents of proposed tax cuts the Australia Institute certainly show that major corporations would have increased profits:

We find that a reduction in company tax to 25 per cent would give Australia’s top 15 listed companies a benefit of $58,075 million over the 10 years from July 2016. Those companies paid $21,742 million in company tax in Australia in the financial year ending in 2015 which amounts to something like a third of total company tax.

For the big four banks a reduction in company tax to 25 per cent would mean a benefit of $2,019 million in 2016-17 and $29,711 million for the decade starting that year. The Commonwealth Bank alone would receive benefits worth around $623 million in 2016-17 and a staggering $9,159 million over the decade (David Richardson 2015, iii)

But we can’t really know what they will do with this money. We can be fairly confident that they will use it to try to generate more profits via investments that return at least the average rate of profit. However global interest rates are so low that capital is cheap to come by – what is lacking are the potential profitable investments. We don’t know if they exist, what they will be or where they are. Also how does the state deal with the decline in revenue? Will a rise in the GST be enough to both pay down debt and create the capacity to offset the cuts to company tax. Will the state need to cut services?

Thus we end up again at a deep knot of contradictions over social reproduction: the need to stimulate and spend simultaneously. There is no obvious way out. Yet at the same time one must give the devil his due: increased taxation on capital may promote some form of capital flight.

Now the point of this isn’t to argue for acquiescence but rather to get a better perspective for struggles. Tax policy is subordinate to capital accumulation. Social Democratic and Left arguments that locate themselves within the illusion of a possible good capitalism are missing the point.

It also means that struggles over social reproduction that further increased the disparity between the state’s revenue and expenditure further exacerbate the crisis of capitalism. We need to own this understanding and everything that flows from that. The ability of capital to imagine future profits tomorrow is really its own sense of its power over labour today. The more we can assert our interests the more we threaten capital accumulation.

Debt, Finance & Accumulation

Since the start of neoliberalism states (along with households and firms) have increasingly funded themselves through debt as well as financial speculation(Streek 2014, 35). The eruption of the crisis and the subsequent bailing out the financial sector generated the current sovereign debt crisis. State debt now itself appears as a source of instability. There is no magic number, no line on a graph, that details how much debt a nation can get into or how large as a percentage or as a nominal amount both debts and deficits can be before everything falls apart. States, like peoples and companies, can continue to borrow as long as lenders believe that lending to them is a profitable activity. The US for example, as the world’s preeminent global power, just continues to borrow and constantly finds lenders. For most state’s this is not the case: when they can’t service their debts they face the possibility of default and credit is either restricted or only keeps flowing on the basis of various conditionalities and reforms. There is an undetermined tipping point where states can’t service their debts and struggle to find new borrowers. Yet even before hitting this point increasing debt influences the operation of a state. Even when the nation-state isn’t facing the possibility of default debt shapes its functioning and behavior.

Nation-states always are always ‘just one node in a web of social relations’ (Holloway 2002, 13). It is a creature of this web. Debt is particular form of relationship. Debt is a particular kind of power relationship which constructs a particular kind of existence for the debtor(Lazzarato 2012). When one borrows they access money today on the promises of paying more back tomorrow. Debt is a promise of current and future behavior. Thus debtors are compelled to behave in certain ways that ensures at least the appearance of being a sensible investment, or at least one where the possibilities of profit outweigh the risks. All debtors are thus subjected to evaluation. More precisely the debtor becomes subjected to the evaluation of capital: their choices, behaviors and demeanors must conform to a certain morality.

The debtor is “free”, but his actions, his behavior, are confined to the limits defined by the debt he has entered into. The same is true as much for the individual as for a population or a social group. You are free insofar as you assume the way of life (consumption, work, public spending, taxes, etc.) compatible with reimbursement.(Lazzarato 2012, 31)

For nation-states this evaluation is the evaluation of rating agencies specifically and the financial markets more broadly. Rating agencies explicitly score states whilst the financial markets operating through the ‘mimetic rationality of ‘herd behaviour’ also pass their judgement(Marazzi 2008, 21). Of course no single national state stands in isolation. The global health of capitalism and global developments come into play. ‘Since 2007, global debt has grown by $57 trillion, raising the ratio of debt to GDP by 17 percentage points’ (McKinsey Global Institute 2015, vi). In a historical moment where many states appeared to struggle to pay their debts all states are compelled to act as good debtors even as they appear to be safer investments. Capital is paranoid about contagion.

Simultaneously state debt, which takes the form of bonds, functions as the ‘bedrock of financial markets’(Lapavitsas 2013, 166). These bonds are both profitable assets in and of themselves but also work as a key element of the pricing of financial assets on a whole. The attempts to make state debts sustainable are attempts to secure their value and reduce the volatility of financial markets.

The Australian Organization of Financial Management which issues Australian state bonds explains their dual goal as follows:

The main objective of Treasury Bond and Treasury Indexed Bond issuance is to raise monies to fund the Australian Government Budget.

Another objective is to support the efficient ongoing operation of Australia’s financial market. This second objective is achieved in the following ways:

- Treasury Bonds, Treasury Indexed Bonds and Treasury Bond futures are used by financial market participants as benchmarks for the pricing of other capital market instruments and to manage interest rate risk; and

- the existence of active and efficient physical and futures markets for sovereign debt strengthens the robustness of the financial system and reduces its vulnerability to shocks. (2015, 9)

This other role that debt has as a source of profit and necessary element of the financial system means that contemporary capitalism requires there to be state debt. A review conducted under then Treasurer Swann detailed that it is optimal for the total value of bonds to be between 12-14% of GDP – thus assuming GDP grows state debt in monetary terms needs to grow too (Koukoulas 2012). This stat though can be misleading as it sees the optimal level of debt to GDP as a simple technical matter – like all these questions it needs to be grasped in the context of the unfolding of the dynamics of capital accumulation and class struggle.

As mentioned Australia’s debt is low by international standards. Under Howard and Costello the high revenues of the mining boom and incomes generated from privatization gave the Commonwealth the capacity to actual pay off all outstanding bonds. Koukoulas (2012)argues that whilst the then Treasurer Costello wanted to pay off Australian sovereign debt once and for all the government didn’t due to the crucial role state bonds play in the market. The very idea itself was critiqued by representatives of finance capital (Letts 2002).

Perhaps it is correct to see this as another way that the state facilitates the reproduction of capitalist society. Luxemburg’s (2003) corrective to Marx’s schema of reproduction points out capitalism can only work with the continual production and circulation of money. In our society money is bank fiat money back by the state and the health of finance capital is key to its functioning. As Marazzi points out in capitalism today finance is cosubstaintial with the very production of goods and services’(2011, 28). Maintaining the health of financial markets is necessary to ensure the continual operation of money and capital accumulation.

But this doesn’t mean that all increases in state debt are good for capitalism. Rather state debt that is seen as being out of control threatens its dual role as asset and key element of pricing. If state debt hits a point which causes it credit rate to drop and investors to flee this both lowers the value of already issued bonds (as the bonds offered at a lower credit rating will normally have a higher interest rate attached to them and the market price of the former will also decline) and generate instability across financial markets.

As I write Australia’s credit rating holds stable however managing this rating remains a concern for all those invested in maintaining the health of capitalism.

Conclusion

At this point we can see the lines of struggle that mark debt and social reproduction. Capitalism requires the state to carry out and/or facilitate many of the tasks of social reproduction. But this costs. The level of social reproduction itself is not a given but a product of class struggle. The increased funding of social reproduction in part by debt is a product of the multitude’s intransience and the inability of the Australian state to force a generalised lower standard of living on the population. It is a product of both the global crisis of capitalism and the inability to make us sufficiently ‘flexible’. So too whilst this debt is a necessary and profitable part of the entire assemblage of accumulation it also contains the possibility of increased meltdowns and malfunctions.

As the mining boom ends the state is called on to carry out multiple, contradictory and risk infused tasks. It must try to stimulate capital accumulation, it must secure the viability of financial markets, it must manage and perhaps even pay down state debt and it must pay for social reproduction. This is probably impossible. Our struggles to assert our own interests and desires are both the ultimate source of these contradicts and exacerbate them. Any victory for our dignity will lead to increase malfunction of the state and of capital accumulation generally.

When the Abbot Coalition Government was elected they brought with them a clear strategy backed by substantial factions of capital, which I have called Plan A. This called for asset sales and the shift of some of the costs and some of the work of social reproduction onto the wage and into the home: this would generate the capital which would allow the state to service and pay down debt, allow tax cuts and infrastructure investment as a form of stimulation. But this Plan A has been at least partially blocked by the corresponding meltdown of politics in Australia. The vast majority of the 2014-15 Budget didn’t make it through parliament, the Qld state election stymied at least some asset privatisations and a palace coup has replaced Abbot and Hockey with Turnbull and Morrison. At the moment a raft of incoherent Plan Bs are being formulated: money thrown at ‘innovation’, tax cuts for corporations, plans to sell the as yet unfinished National Broadband Network… Whilst a key publication of the political class has a long form essay detailing ‘How We Forgot How to Govern’ (Tingle 2015). It is this break down of ‘the political’ that will be the next subject of my investigation.

Australian Office of Financial Management. 2015. Annual Report 2014-2015: Commonwealth of Australia.

Business Council of Australia. 2015. Bca BudEt Submission 2015–16: A 10-Year Plan for Growth. http://www.bca.com.au [cited 09th March 2015].

Caffentzis, George. 2013. In Letters of Blood and Fire: Work, Machines and the Crisis of Capitalism. Oakland, CA: PM Press.

Daley, J, and D Wood. 2015 Fiscal Challenges for Australia Grattan Institute.

Dalla Costa, Mariarosa, and Selma James. 1975. The Power of Women and the Subversion of the Community. 3rd ed. Bristol: Falling Wall Press.

David Richardson. 2015. Cutting the Company Tax Rate Why Would You?: The Australia Institute,.

Federici, Silvia. 2006. "The Restructuring of Social Reproduction in the United States in the 1970s " The Commoner: A Web Journal For Other Values (11 Spring ):74-88.

Federici, Silvia. 2012. Revolution at Point Zero. Oakland CA: PM Press.

Fortunati, Leopoldina. 1995. The Arcane of Reproduction: Housework, Prostitution, Labour and Capital Translated by H Creek. Brooklyn, NY: Autonomedia.

Hardt, Michael, and Antonio Negri. 2003. Labor of Dionysus: A Critique of the State-Form. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Harper, Professor Ian, Peter Anderson, Su McCluskey, and Michael O’Bryan QC. 2015. Competition Policy Review Final Report Commonwealth of Australia

Holloway, John. 2002. Change the World without Taking Power: The Meaning of Revolution Today. London: Pluto Press.

International Monetary Fund. 2015. Imf Country Report No. 15/274 Australia 2015 Article Iv Consultation—Press Release; Staff Report; and Statement by the Executive Director for Australia.

Joye, Christopher. 2015. Federal Budget 2015: Worst Cumulative Deficits in 60 Years. Australian Financial Review [cited 27th October 2015]. Available from http://www.afr.com/news/policy/budget/federal-budget-2015-worst-cumulative-deficits-in-60-years-20150505-gguuug - ixzz3pjpoczB7

Katsarova, Rada. 2015. Repression and Resistance on the Terrain of Social Reproduction: Historical Trajectories, Contemporary Openings. Viewpoint Magazine (5), https://viewpointmag.com/2015/10/31/repression-and-resistance-on-the-terrain-of-social-reproduction-historical-trajectories-contemporary-openings/.

Koukoulas, Stephen. 2012. Why Government Debt Must Grow Forever. Business Spectator [cited 2nd November 2015]. Available from http://www.businessspectator.com.au/article/2012/11/2/interest-rates/why-government-debt-must-grow-forever.

Lapavitsas, Costas. 2013. Profiting without Producing: How Finance Exploits Us All. London & New York: Verso.

Lazzarato, Maurizio. 2012. The Making of Indebted Man: An Essay on the Neoliberal Condition. Translated by Joshua David Jordan. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e).

Letts, Steve. 2002. Markets Criticise Plan to Scrap Government Bonds. Lateline [cited 4th November 2015]. Available from http://www.abc.net.au/lateline/stories/s715242.htm.

Lorey, Isabell. 2015. State of Insecurity: Government of the Precarious. London & Brooklyn, NY: Verso.

Luxemburg, Rosa. 2003. The Accumulation of Capital. Translated by Agnes Schwarzschild. London & New York: Routledge.

Marazzi, Christian. 2008. Capital and Language: From the New Economy to the War Economy. Translated by Gregory Conti. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e).

Marazzi, Christian. 2011. The Violence of Financial Capitalism. New ed. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e).

Marx, Karl. 1990. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Translated by Ben Fowkes. Vol. 1. London: Penguin Classics.

Marx, Karl. 1991. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Translated by David Fernbach. Vol. 3. London: Penguin Books in association with New Left Review.

McKinsey Global Institute. 2015. Debt and (Not Much) Deleveraging: McKinsey & Company.

Parliamentary Budget Office. 2015. 2015-16 Budget: Medium-Term Projections: Parliamentary Budget Office,.

Passant, John. 2015. Raising the Gst Will Hurt Workers and the Poor: There Are Other, Fairer Options. Independent Australia [cited 26th November 2015]. Available from https://independentaustralia.net/politics/politics-display/raising-the-gst-will-hurt-workers-and-the-poor-there-are-other-better-options,8335.

PwC. 2015. Company Tax Cuts Help the Economy and Real Incomes Grow [cited 8th December 2015]. Available from http://www.pwc.com.au/press-room/2015/company-tax-cuts-nov15.html.

Shortall, Felton C. 1994. The Incomplete Marx. Aldershot, England Avebury.

Streek, Wolfgang. 2014. "How Will Capitalism End." New Left Review (87):35-64.

The Australian Government the Treasury. 2015. Re:Think Tax Discussion Paper March 2015: Commonwealth of Australia.

The National Commission of Audit. 2014. Towards Responsible Government the Report of the National Commission of Audit Phase One: Commonwealth of Australia.

Tietze, Tad, and Elizabeth Humphrys. 2015. Anti-Politics and the Illusions of Neoliberalism. Oxford Left Review (14), http://oxfordleftreview.com/olr-issue-14/tad-tietze-and-elizabeth-hymphreys-anti-politics-and-the-illusions-of-neoliberalism/.

Tingle, Laura. 2015. "Political Amnesia: How We Forgot How to Govern." Quarterly Essay (60):1-85.

[i] Here the terms ‘reproduction of society’ and ‘social reproduction’ are used interchangeably. On the concept of concept of ‘social reproduction’ see Katsarova (2015) and the entire latest issue of Viewpoint Magazine

[ii] I am indebted to Rob and Rascal for these insights.

(

( (

(

Comments